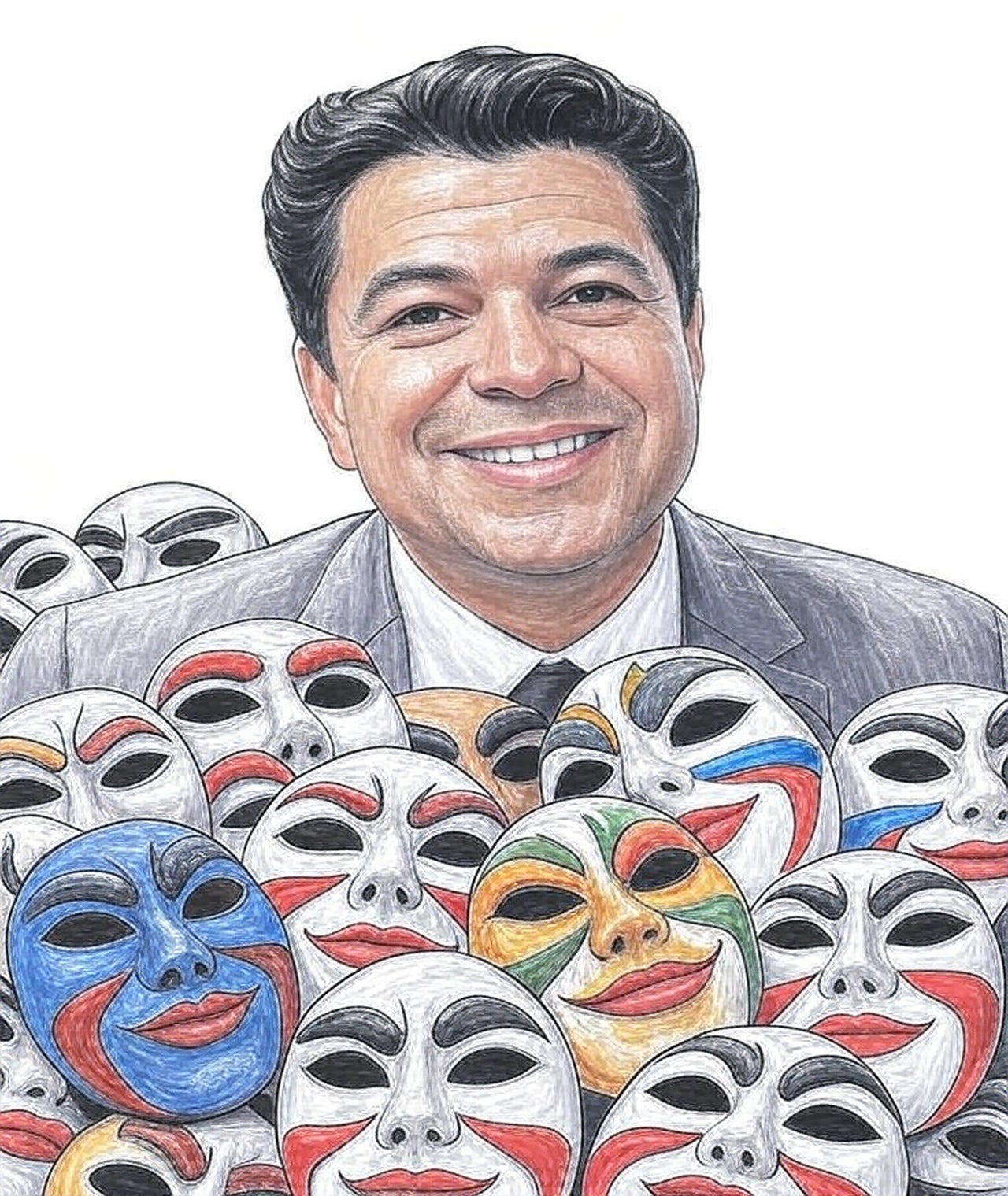

Ross Martin, the Chameleon of the Screen, and the Complex Legacy of His Ethnic Portrayals

NEW YORK, May 4, 2025 – In the summer of 1981, Ross Martin collapsed on a tennis court in Ramona, California, his heart giving way under the scorching sun. The 61-year-old actor, whose face was as familiar to television audiences as the flickering glow of their sets, left behind a career that spanned over three decades and more than 200 productions. Best known as Artemus Gordon, the master of disguise in CBS’s The Wild Wild West, Martin was a chameleon of the screen, a man who could slip into any role, any accent, any ethnicity with an ease that captivated audiences and confounded casting directors. But in an era when Hollywood’s approach to representation was often cavalier, Martin’s ability to portray any ethnicity—rooted in his multilingual upbringing and theatrical genius—raises questions that resonate today. Who was Ross Martin, and what does his legacy teach us about talent, versatility, and the ethics of performance?

Born Martin Rosenblatt on March 22, 1920, in Grodek, Poland, Martin was an infant when his Jewish family boarded the steamship New Rochelle and arrived at Ellis Island in September 1920. Settling on New York City’s Lower East Side, a crucible of immigrant cultures, young Martin grew up amid a symphony of languages—Yiddish, Polish, Russian, and Italian from his playmates. He didn’t learn English until age five, later adding French, Spanish, and Italian to his repertoire. This linguistic dexterity, honed in the tenements of Manhattan, would become the bedrock of his acting career. A violin virtuoso by age eight, performing with a junior symphony orchestra, Martin was also a scholar, graduating magna cum laude from City College of New York and earning a law degree from the National University School of Law. Yet, despite honors in business, instruction, and law, the stage called louder than the courtroom.

Martin’s early career was a testament to his restless talent. In the 1930s, he performed as half of the vaudeville comedy duo “Ross & West” with Bernard West, sharpening his comedic timing. By his 20s, his knack for dialects landed him roles in radio, where he juggled three daytime serials simultaneously, including a 62-year-old Viennese gentleman. His Broadway debut came in 1953 with Hazel Flagg, a musical adaptation of Nothing Sacred. But it was television and film that would make him a household name. His first film, George Pal’s Conquest of Space (1955), marked his entry into Hollywood, followed by a string of roles under director Blake Edwards. Edwards cast him as Sal in a 1959 Peter Gunn episode, the asthmatic kidnapper Red Lynch in Experiment in Terror (1962), for which he earned a Golden Globe nomination, and the cunning Baron Rolfe Von Stuppe in The Great Race (1965). These roles showcased Martin’s range, from menacing to comedic, and cemented his reputation as a character actor par excellence.

It was The Wild Wild West (1965–1969) that defined Martin’s career. As Artemus Gordon, the gadgeteer and disguise artist alongside Robert Conrad’s James T. West, Martin became a fan favorite. The role was a perfect fit: Gordon’s weekly transformations into characters of varying ethnicities and backgrounds allowed Martin to flex his linguistic and theatrical muscles. He designed many of Gordon’s disguises himself, sketching make-up designs as early as the pilot episode. Whether posing as a Mexican bandit, a Chinese merchant, or a Native American chief, Martin’s performances were seamless, often leaving castmates unaware of his appearance until filming began. “I went home one afternoon to pick up a script without bothering to change,” Martin once quipped, “and a half hour later the Beverly Hills Police were at my door because a neighbor reported a suspicious stranger lurking around Ross Martin’s house. I had to peel off my beard to prove who I was.” His ability to vanish into his roles was both his greatest asset and, in retrospect, a point of contention.

Martin’s multilingual background was central to his versatility. Growing up in a polyglot neighborhood, he absorbed accents and mannerisms with an almost anthropological precision. On The Wild Wild West, he used his command of Spanish, French, and Italian to lend authenticity to his disguises, while his Yiddish and Polish roots informed his portrayal of Eastern European characters. His radio experience, where he once played an elderly Viennese gent, honed his ability to manipulate voice and inflection. This skill extended to roles beyond The Wild Wild West. In a 1973 TV movie, The Return of Charlie Chan, Martin played the iconic Asian detective, a role that sparked protests from Asian actors’ groups who decried the casting of a non-Asian actor. Similarly, his portrayal of an Arab sheik in a 1976 Sanford and Son episode, while played for laughs, reflects the era’s casual approach to ethnic casting. These performances, though critically praised at the time, are now viewed through a lens of cultural sensitivity, highlighting the fine line Martin walked between artistry and appropriation.

The 1950s to 1970s Hollywood landscape Martin navigated was one of limited diversity and lax standards for authentic representation. Non-white roles were frequently played by white actors in make-up, a practice known as “yellowface” for Asian characters or similar techniques for other ethnicities. Martin, with his linguistic prowess and theatrical training, was a go-to choice for such roles. His Jewish immigrant background, paradoxically, may have made him an “outsider” in Hollywood’s eyes, aligning him with characters deemed “exotic.” Yet, his performances were not mere caricatures; they were layered, often imbued with a humanity that transcended the scripts. In Experiment in Terror, his Red Lynch was a chillingly real villain, his asthmatic wheeze a haunting signature. In The Great Race, his Baron Von Stuppe was a deliciously sly antagonist, stealing scenes with a twinkle in his eye. Martin’s ability to elevate even problematic roles speaks to his craft, but it also underscores the industry’s reliance on versatile actors to fill gaps left by systemic exclusion.

Martin’s career was not without setbacks. In 1968, during the filming of The Wild Wild West, he suffered a near-fatal heart attack, compounded by a broken leg, forcing the show to replace him with actors like Charles Aidman and William Schallert for nine episodes. The series, canceled in 1969 amid a national debate over television violence, left Martin with an Emmy nomination but a tarnished prospect for lead roles. Networks, wary of his heart condition, relegated him to guest spots, yet Martin’s passion for acting never waned. He appeared in an astonishing array of shows—Columbo, where he played a murderous art critic opposite his former student Peter Falk; Mork and Mindy, as a professional bum in his final role; The Twilight Zone; Charlie’s Angels; and Fantasy Island. He also took to the stage, earning acclaim as John Adams in a 1976 touring production of 1776. His resilience was remarkable, but the heart condition that shadowed his later years culminated in his death on July 3, 1981.

Martin’s guest roles showcased his ethnic versatility in ways both celebrated and scrutinized. In Columbo’s “Suitable for Framing” (1971), his portrayal of a suave art critic leveraged his European sophistication, while in Sanford and Son’s “California Crude,” his Arab sheik played into comedic stereotypes. His attempt to star as Charlie Chan in 1973, though well-received by audiences, was a flashpoint. Asian advocacy groups protested, arguing that casting a white actor perpetuated harmful stereotypes, and plans for a series were scrapped despite strong ratings. Today, such casting decisions would likely face fiercer backlash, as the industry grapples with authentic representation. “Ross Martin was a genius at transformation,” says Dr. Karen Tong, a media studies professor at NYU, “but his era’s casting practices reflect a blind spot we’re still correcting. His talent was undeniable, yet it was often used to fill roles that should have gone to actors of those ethnicities.”

Beyond his screen work, Martin was a mentor and a mensch. He taught acting to Peter Falk, whose interplay with Martin in Columbo and The Great Race crackled with mutual respect. Robert Conrad, his Wild Wild West co-star, mourned him as “a credit to this world,” saying, “If more people were like Ross Martin, it would be a better place to live.” Martin’s kindness extended to charitable causes and his support for fellow actors, often helping them navigate the industry’s challenges. His personal life, marked by his marriage to Muriel Weiss (1941–1965) and later Olavee Grindrod, with whom he adopted two children, reflected his warmth. He had one daughter from his first marriage and remained a devoted father. His love for music, evident in his childhood violin performances, occasionally surfaced in roles, such as a Wild Wild West episode where he played the instrument.

Martin’s legacy is a paradox: a testament to unparalleled talent and a reminder of Hollywood’s past missteps. His ability to portray any ethnicity was a product of his unique upbringing and skill, but it was also enabled by an industry that prioritized versatility over authenticity. Modern critics admire his craft while acknowledging the discomfort of roles like Charlie Chan. “Martin’s performances were transformative, but they existed in a vacuum of opportunity for actors of color,” notes Tong. His work on The Wild Wild West remains a high point, with fans on platforms like X still celebrating his Artemus Gordon as “flawless” and “wonderful.” Yet, his career also prompts reflection on how far the industry has come—and how far it has yet to go.

In today’s Hollywood, where casting prioritizes cultural accuracy, Martin’s story serves as both inspiration and caution. His journey from a Polish immigrant to a television icon underscores the power of resilience and passion. He turned down The Wild Wild West five times, wary of typecasting, but embraced it as “the character actor’s dream,” relishing the chance to play a new role each week. His ability to make every character, from villain to sidekick, unforgettable speaks to a craft honed in the melting pot of New York and the crucible of Hollywood. Yet, his ethnic portrayals remind us that talent, no matter how prodigious, must be wielded with care in a world that demands equity.

Ross Martin’s life ended too soon, but his impact endures. He was a man of many faces, each one a testament to a career that pushed boundaries and broke molds. As we revisit his work, from the gadget-laden train of The Wild Wild West to the shadowy streets of Experiment in Terror, we see not just an actor, but a storyteller who wove his own immigrant experience into every role. His legacy challenges us to celebrate the artistry of transformation while striving for a future where every face on screen reflects the world as it is. In the words of his friend Conrad, Ross Martin made the world a better place—one disguise, one dialect, one unforgettable performance at a time.