“The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour," which ran on CBS from February 5, 1967, to April 20, 1969, remains a towering achievement in television history—a variety show that redefined the medium by blending comedy, music, and unapologetic social critique into a singular, electrifying package. Hosted by Tom and Dick Smothers, a folk-singing duo with a knack for sibling rivalry turned comedic gold, the program arrived at a pivotal moment in American culture. The late 1960s were a cauldron of unrest—Vietnam War protests, civil rights marches, and a burgeoning counterculture clashing with the old guard—and the Smothers Brothers didn’t just reflect this upheaval; they amplified it, wielding humor as both a scalpel and a sledgehammer. Over its 71 episodes, the show became a battleground for free expression, a showcase for emerging talent, and a lightning rod for controversy, leaving behind a legacy that continues to shape comedy and television to this day.

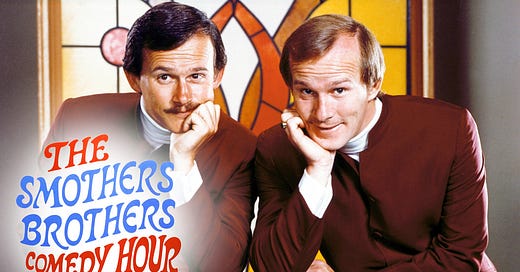

The Smothers Brothers themselves were the linchpin of the show’s appeal. Tom Smothers, with his boyish face, tousled hair, and perpetually befuddled demeanor, played the "dumb" brother—a role he leaned into with such exaggerated charm that it became a masterclass in comedic timing. Dick Smothers, by contrast, was the smooth, rational foil, his bass and deadpan delivery grounding Tom’s flights of fancy. Their act, rooted in folk music performances punctuated by mock arguments and tangents, was deceptively simple. A typical bit might start with a song like "Boil That Cabbage Down," only for Tom to derail it with a rambling diatribe about their mother loving Dick best—a gag that never got old thanks to their chemistry. This dynamic wasn’t just funny; it was relatable, a sibling squabble writ large that invited viewers into their world before the show veered into bolder territory.

And bold it was. "The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour" distinguished itself by diving headfirst into the cultural and political maelstrom of the era. Unlike contemporaries like "The Ed Sullivan Show," which prioritized broad appeal and avoided rocking the boat, the Smothers Brothers embraced satire that cut deep. Sketches took aim at the Vietnam War, with thinly veiled jabs at military brass and politicians; they mocked religious dogma, once prompting outrage from clergy over a bit about a bumbling priest; and they skewered racial and social hypocrisies with a slyness that often slipped past censors—at least initially. The writing team was a murderers’ row of talent: Steve Martin brought his offbeat absurdity, Rob Reiner his knack for character work, Bob Einstein (later Super Dave Osborne) his dry cynicism, and Mason Williams—composer of "Classical Gas"—his poetic edge. Together, they crafted material that was as smart as it was subversive, often cloaking radical ideas in the guise of absurdity.

Recurring segments became cultural touchstones. Pat Paulsen’s "editorials" were a highlight—delivered with a stone-faced gravitas, he’d offer hilariously obtuse takes on issues like gun control ("We should arm everyone, then we’d all be equal") or the war ("Why fight abroad when we can fight right here at home?"). His mock 1968 presidential run, complete with campaign slogans like "If elected, I will not serve," was so convincing that some viewers reportedly tried to vote for him. Another gem was Leigh French’s "Share a Little Tea with Goldie," a hippie caricature who dispensed "advice" laced with double entendres about marijuana—subtle enough to dodge early censorship but blatant to anyone paying attention. These bits didn’t just entertain; they challenged viewers to think, laugh, and occasionally squirm.

The musical roster was equally fearless, reflecting the era’s sonic revolution. The show booked folk legends like Pete Seeger, whose 1967 performance of "Waist Deep in the Big Muddy"—a haunting anti-war parable—was famously cut by CBS, only to be reinstated in 1968 after public backlash. Joan Baez dedicated songs to her draft-dodging husband, while Harry Belafonte’s soulful presence carried unspoken weight amid civil rights struggles. Rock acts like The Who (whose drum-explosion incident left Tom quipping, "Well, that’s one way to end a song") and Jefferson Airplane brought raw energy, while pop stars like Nancy Sinatra added mainstream gloss. Each performance was curated to resonate with the show’s ethos—music wasn’t just filler; it was a megaphone for the message.

This audacity, however, put the show on a collision course with CBS. The network’s Standards and Practices department became the Smothers Brothers’ nemesis, scrutinizing scripts with a zeal that bordered on paranoia. A 1967 sketch about a censor being outwitted by a comedian was ironically censored itself. References to drugs, sex, or anything deemed "anti-American" were slashed—sometimes hours before airtime. Tom, the creative force behind the show, fought back, arguing that comedy should provoke, not pacify. The tension peaked in 1969 when CBS axed the program, citing a missed tape delivery deadline—a flimsy excuse for what was really a purge of a show that had become too hot to handle. The Smothers Brothers sued for breach of contract and won $776,000, but the victory was bittersweet; the cancellation killed their momentum, though it burnished their legend as martyrs for artistic freedom.

The production itself was a product of its time—modest sets, live audiences, and a rough-around-the-edges feel that contrasted with today’s polished TV. Sketches could drag, and some humor (like occasional racial or gender gags) lands awkwardly now. Yet, these imperfections only enhance its authenticity. The show’s influence is undeniable: it birthed a lineage of boundary-pushing programs—"Saturday Night Live," "Chappelle’s Show," "The Daily Show"—and launched careers that defined comedy for decades. Its 20 Emmy nominations (and one win for writing) underscore its critical heft, but its real triumph was cultural: it proved TV could be a platform for dissent, not just distraction.

"The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour" is a time capsule of the late ’60s—a chaotic, hopeful, angry era mirrored in its every frame. It’s a love letter to irreverence, a middle finger to conformity, and a testament to the power of laughter in dark times. For modern viewers, episodes (scattered across DVDs, YouTube, or rare reruns) offer a glimpse into a moment when two brothers with musical instruments dared to speak truth to power—and got away with it, until they didn’t. It’s not always polished, not always perfect, but it’s always alive. Dive in, and you’ll find a show that’s as infuriating, inspiring, and hilarious as the age it captured.